Talking to someone in the comments on the most recent comic I’ve posted up made me realize that the term “Mary Sue” or “Gary Stu” is being thrown around awfully liberally these days. As much as “hipster” seems to mean “young adult who wears clothing”, all it seems to take for a character to rack up accusations of being a wish-fulfillment mouthpiece device is to be the same gender as the writer, be notably talented at anything, or be likeable in any way. In light of this, I went back to the archives and found a blog post I wrote about two years ago for my on-again-off-again dead and reanimated and dead all over again art blog regarding writing interesting protagonists in a fantasy or sci-fi setting. I’ve cannibalized it a bit, but if it seems familiar that may be why.

I know the vast internet collective has coded up plenty of “is your character a Sue” tests that people run to so they can gauge whether or not their characters are ordinary enough to make the grade. I always feel on the fence about these kind of tests because the traits they call out are almost completely irrelevant outside of the context and actual application they receive in the piece. What may seem unacceptably fantastic in theory may be considered mundane when viewed in the actual scope of the world a writer has built. And just because something sounds idealized when you break it down into the individual pieces, it doesn’t necessarily mean that those features manifest in a particularly flattering manner.

For example, let’s say I describe a character to you as a broody, dark skinned man in impeccable physical condition with pointy ears, long white hair, purple eyes, and an aptitude for bladed weapons. Clearly I must be talking about that pretty-boy drow prince, Drizzt, from Forgotten Realms.

Oh wait no, I was actually talking about Sten.

That’s the difference context and application make.

I absolutely hate the question “is the character attractive” because there is such a massive scope of what people are attracted to that you can take just about anything you can think of and someone out there will find downright sexy. Think Marv from Sin City, the driving force behind that character is supposed to be that he is so ugly and horrible, even in a city of prostitutes only one woman has ever agreed to sleep with him. I could probably find you a handful of women who would argue that Marv is more attractive than Mickey Rourke under normal circumstances and even more who would be all over a guy like that in real life.

For that matter, are guys like Steve Buscemi attractive? He’s been married for 23 years, obviously someone digs him.

If I make a Steve Buscemi-inspired character and some fan draws steamy anime-styled porn of them with lots of cherry blossoms and drapey fabric because they think he’s so gawgeous and wonderful, does that mean I’ve just designed an attractive character? From my experience, no matter what a character looks like, if you make them out to be sympathetic or friendly in any way someone out there will assume that they must either be the kind of person you’re attracted to or the kind of person you wish you could be.

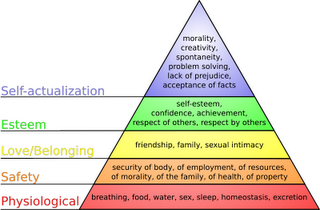

My favourite subject to write about basically breaks down to outlandish characters doing mundane things (as you may have noticed from this webcomic here that I assume you’ve been reading). I am of the opinion that there is no character out there so outlandish and out of touch that they couldn’t be recrafted into a relatable person by taking Maslow’s Pyramid of Human Needs into account.

This pyramid represents the basic concerns of a human being in ascending order of triviality. The lowest levels of the pyramid represent the lowest common denominator that all people can identify with. As you climb the pyramid, problems will generally matter less.

The bottom of the pyramid represents life-or-death needs like food, water, shelter, air. No one in the world will ever question a character’s motivation to not die. And when they say “sex” they mean it in a Children of Men “our species is going to die” way that drives characters in a post apocalyptic setting to muse about how the earth will be repopulated, not the “bawww why can’t I get laid” way. In the context of films like 28 Days Later where they take into account what that drive to preserve the species will do to women’s rights, it’s downright terrifying. Matters of life and death will always interest an audience, so even a character who sits at a high level on the pyramid can be stripped down to a basic need for survival in the climax of a story.

Less important than air, but still of pretty high concern is safety. The feeling of unease walking home alone at night, fear of losing your job, and health issues are all fairly universally accepted as important motivations and can easily turn into life or death struggles in their own rite.

Love or belonging is a fairly light, inoffensive problem for a character to overcome. On it’s own, it’s a status more suited for comedy, as it lacks the drama of life-or-death struggles.

Respect amongst one’s peers is in a similar boat, and is the last really relatable struggle you can put your character through. Self-actualization is more of an abstract idea that can lose your audience, as a character whose only struggle is to be the best at what they do is not terribly entertaining if they can’t be stripped down to a more basic need in the pursuit of that goal.

Conflict is built out of characters gambling their place on the pyramid as they attempt to raise their status, and characters cannot climb to a higher level if the needs below them have not been met. For example, a character will not be worried about getting the girl if they are in the middle of drowning (unless they are possibly Leonardo DiCaprio). The more a character stands to lose, the more an audience will care about them. This is why the first Iron Man is more entertaining in every way compared to that abortion of a sequel it got. Iron Man the first saw Tony Stark as a Millionaire jackass playboy who is humbled to a life or death struggle when his convoy is bombed and he’s left dying in the desert with shrapnel in his heart. He can’t be the life of the party again until he can figure out a way to improve on the car-battery system they rigged up in his chest to give him a few days to live. And his cocky attitude remained dampened until he could escape the terrorists who were planning to execute him after he was finished with their bidding. His security was stripped away when he found that the man who had ostensibly become his father figure was doing shady things with the company behind his back and trying to force him out, and that soon became and all new life-or death struggle of it’s own right.

The second Iron Man hit it’s climax somewhere around the 20 minute mark When Tony fights Vanko at the race because that is the only point where he’s truly caught off guard and seems concerned for his life. We’re told that he’s allegedly dying, but it comes across as more of a tacked on plot device than a legitimate concern because it doesn’t seem to distract from Tony’s illustrious lifestyle. The writers threw away every opportunity they had to strip him down to an interesting conflict. Tony’s got some blood poisoning from his chest reactor and it throws him into a funk. He takes his armour on a drunken joyride through a house party and what could have been an opportunity to have him, say, accidentally harm a guest and end up mired in legal ramifications that threaten his adoration from the public and security in the company while he’s simultaneously dealing with the medical trainwreck he’s becoming turns into an opportunity to show off how nice their CG super suits look when they fight to a catchy soundtrack that I’m sure was very expensive to license. Then before the whole “dying” thing can really bring him down to some base emotions, like a modern day Perseus people start showing up and handing him the solutions to every issue that might have been interesting to watch him overcome.

I guess what I’m getting at is that people can’t be all that concerned about your character if the character doesn’t seem to be concerned about themselves. There are a lot of stories you head into knowing that the Good Guys will win and the Bad Guys will lose, but those stories are still entertaining when you don’t know HOW the Good guy will win. If it’s because the good guy is super smart and rich and sexyfine and gets all the girls and everybody wants to be his best pal and he’s totally confident with himself and the Bad Guys are ugly poor losers and nobody likes them, you just wrote a really boring story. The whole conflict is so one-sided, people are probably going to start feeling more sympathy for the Bad Guys. Things are stacked against them but they still keep fighting so whatever it is they’re after must be pretty important. (Call the story Megamind and expect to see $150 million at the domestic box office)

People are quick to call “Mary Sue” on characters they feel are overpowered, but the problem with these characters is not in their copious volume of powers, it relates back to the pyramid as well. “Mary Sue” characters are generally boring because they’re rich and everyone wants to be their friend and they have a smoking hot significant other and they’re the best at what they do. They’re already at the top, so their story has no room to arc. A protagonist can have rainbow hair, fourteen wings, and laser beams shooting from their purple eyes and still be interesting to read about if they have some kind of real human struggle in their life that the audience can connect with.

My favourite example of this is John Arcudi’s short-run DC comic, Major Bummer. Lou Martin is a tall, handsome, indestructible superhero with inhuman strength, super genius engineering skills, and a chiseled body that makes smoking hot women fight over him. On the other hand, he’s always losing his jobs at fast food restaurants and VCR repair shops when his bosses are angry about having to clean up after his massively destructive battles at work, catty women are constantly trying to manipulate his life to get cozy with him, his massive bulk is too big to fit in the crappy car his unemployed ass can barely afford, the horrible lizard people he brutalizes in the effort to not-get-killed-by take him to court with assault charges, and he can’t sleep in on the weekends because people assume being a hulking demigod means he’s obligated to get up early and save the city from whatever Nazi dinosaur threat has them in peril that week.

I also see it suggested quite frequently that if a character has similar beliefs, ideals, or opinions to the writer, the character is by default a mouthpiece. I don’t think this is necessarily the case. True, if the point of the character is to beat down strawmen in one-sided debates regarding issues near and dear to to the author’s heart, that’s about as soapboxey as it gets. However, I think for a writer to create a character that is even the slightest bit interesting, they have to put at least a little bit of themselves into it. It ties into the old saying that you have to write what you know.

If a writer makes a character that they completely disagree with on every front and cannot empathize with at all, that character is likely going to end up being the aforementioned strawman and the anyone who interacts with them, allowed to have a real human thought process, is going to seem like a mouthpiece by default. I’m not saying that a person has to agree with what a character thinks, but they should relate to them enough to understand why they would think like that. For example, if a story calls for a character to make a racist remark it’s easy enough to invent a one dimensional player who exists solely to say inappropriate things and be put back on the shelf. On the other hand, if you put some effort into figuring out why that particular character would say something like that you add another layer to them. It could be upbringing, or a violent run-in with some people of whatever group they’re prejudiced against, or a high-tension situation that made them say something they’ll regret later, or even just something volatile the character likes to do to watch how it makes other people uncomfortable. The writer can completely disagree with everything their creation just said or did, but they still put enough of themselves into it to rationalize the exchange from a different point of view. I’ve scripted out whole arguments before that were just based on me playing devil’s advocate in my own head. Neither side agreed with what the other was saying even though both were rationalized by the same person.

What it basically comes down to is that writing fantasy stories is like drawing fantasy creatures. Dragons may not exist, but people can tell if a drawing of one is believable or “realistic” based on how well the image seems to relate to what they know actual animals look like in real life. In the exact same way, the stories that stick around are the ones people can relate to real situations.

Discussion (140) ¬

Awesome.

Especially the use of Maslow’s Pyramid.

However, I think having an ultimate over-powerful secondary character can be very interesting.

It might work even with the main character; it’s all about what you’re sharing and what people are expecting from your story.

The omnipotent (or darn close to it) character is done all the time! You’re right, they’re very interesting. Example: Dr. Manhattan.

I would argue that despite his omnipotence Dr. Manhattan still has a conflict regarding how his sense of belonging is affected by the ghost of his human nature. As he tells Laurie, he’s obviously still affected in some way by losing her because when she leaves him, he leaves the planet. Some part of him still wants that companionship but he’s too distant and removed from humanity for anyone to properly reciprocate.

I think that’s what sadleric meant– and I agree, there is “room to arc.” Very nicely done essay! This should be linked on tvtropes dot com . If you haven’t been there, then you’re missing out. Don’t go unless you have an hour or two to surf! (It isn’t a waste, trust me… :3)

Also Silver Age Superman, the Doctor from Doctor Who, and Death from the Discworld series.

It’s long seemed to me that, when writing a nigh-omnipotent protagonist, the question isn’t so much what the character is capable of doing but what the character is willing to do; since the hero can utterly destroy any external source of conflict, the story’s conflict has to come from within — and the more inner struggles such a character faces, the better.

Your average Star Trek captain wields technobabble like a magic wand, but of course they have to deal with issues of morality, self-doubt, and upholding the Prime Directive, so the plot’s tension often comes from persuading them to overcome their personal misgivings even if they actually go about solving the problem by “running a polarized neutrino beam through the warp conduits” or something equally retarded. The Doctor is practically immortal, superhumanly intelligent, and has both a time machine and a literal magic wand, but he’s an emotionally broken man who struggles under the weight of his responsibilities and loneliness. The trick, I guess, is to point these characters at problems they can’t resolve without facing down their own inner demons.

I hadn’t thought of tying this to the Hierarchy of Needs, though. Clever move, Coelasquid.

It doesn’t even need to be inner demons, the Doctor still has things that mortally threaten him or the people he’s trying to save that won’t offer him any easy outs. It’s sort of like video game logic, just because you got an extra life doesn’t mean you’re any better at playing the game, it just gives you more time to figure out what not to do.

I suppose, although it’s pretty uncommon for the monster of the week to pose a credible threat to the Doctor’s survival (especially because aargh they never actually shoot him when they have the chance). And even when they do, he still has to work around his inner obstacles — his pacifism, his desire to act as savior to a species that doesn’t always appreciate his help, etc. — which limit the sort of solutions he allows himself to use.

Granted, I’m not a huge Doctor Who fan, but the episodes that stand out in my head are ones like the stone angel ones, the thing in the library that was stripping everyone down to skeletons inside their space suits, the water zombies, and the things that started ripping apart reality because they messed with Rose’s father’s death. All of which were legitimate life or death threats to the people involved. If the only thing holding a character back is their inner turmoil, they’re going to become increasingly angsty and frustrating. Where a character going against their morals becomes interesting is in the consequences that come out of it. Like in the waters of Mars, the Doctor isn’t supposed to mess with these fixed points. He could theoretically, but he doesn’t because those are the rules I guess. And when he does decide “Screw the rules! I’m the Doctor!” and meddles with it, he ends up making things worse. If he just broke his rules and nothing went wrong it would be more of a case of “Why didn’t I do that sooner? Now I feel silly.” and that just wouldn’t carry the same impact.

Good examples, although when I think of an episode that really threatened the Doctor’s life I recall the one where he’s trapped inside a tour bus with a bunch of increasingly paranoid tourists and a presence that caused them to repeat each other’s words. Remember that one? That episode was boss.

Anyways, your point re: Waters of Mars is well-taken. Perhaps that’s the golden rule for writing plausible nigh-omnipotent protagonists: occasionally drive home the fact that the difference between a nigh- and totally omnipotent protagonist is that a nigh-omnipotent protagonist can occasionally bend the rules, but outright breaking them will come back to bite him in the ass.

And there’s no better defense against accusations of Mary-Sueism than allowing your protagonist’s bad decisions catch up with him now and again.

At any rate, I’ll agree with this: without some sort of external rules constraining the protagonist’s actions, you end up with a.) a character who’s so internally conflicted he’s completely unrelatable or b.) Axe Cop.

It will be interesting to see what happens with Axe Cop when the kid writing it gets old enough to understand exactly what’s going on. I mean… there’s a very narrow window in their lives where people sincerely write like five-year-olds…

but what about conan the barbarian(the original robin e howard stories), while hes not the most powerful thing in his universe

hes pretty darn godly in his physical strength and combat and there was only one normal human that was physically strong enough to be a close match for him(the strangler dude), and he has no conflicts or issues, he just kicks ass and the character was very sucessful.

Conan doesn’t read like a five year old wrote him.

Anyway, yeah, I’ve wondered about this before too, because Conan is pretty much the best around but I still love Conan stories. I think a lot of it has to do with his self-imposed “I have to be king by my own hand” thing. It’s a clear goal he has to work towards, and often when he starts getting close (queens wanting to marry him and the like) he puts the brakes on and runs off to start at square one again because he won’t accept it if he didn’t do it himself. I’ll concede I’ve only read the old Savage sword of Conan comics, but he’s enough of a drifter that he always has to travel light. He’ll be the general of an army with everything he could ask for, then the job will start ending and he has no mind for conserving resources so he’s right back to wandering around the desert in his manties the next issue. Plus, the local fauna till challenges him. Dragons are hard enough to kill that he gets chased up hills by them and runs away when they go after him. And he can only take so many hits before he’s laid up in the infirmary, the Savage Sword stuff really treats him like more of a rogue than a brawler, he’s more about sneaking through the backdoor than running headlong into people. I think there was even a story where he spends too long looking for a way to infiltrate a gang of marauders and unwittingly lets his old love interest that he had been coming home to marry die.

And there’s that old Conan staple of being crucified and ripping throats out of vultures with his teeth to drink the blood and stay alive. That’s a pretty daunting life or death challenge, characters are allowed to have challenges and still be badass.

hmm it wont let me reply to what you said. oh well ill put it here. I only mentioned the original stories because thats all i read, but this stuff sounds pretty close to him. Ironically i just read that some people thought he was robin e howards ideal self. I mean all men would like to be conan.

Personally i think that fiction doesnt really have any rules to make it good, its just dumb luck and yeah some skill.

gee i wish i could edit that. it takes more than just some skill. a lot of skill. i couldnt write anything good(you may have noticed my punctuation sucks). but still it seems like a lot of dudes go and create something thats a hit, and then create other stuff but they dont seem to realise what made the first thing so perfect. especially in videogames. course some people do know how to make tons of good stuff but they cant tell you how they do it.l

There are actually pretty clear structures for how good stories work. Writing is like drawing, no matter what style you’re working in there are very clear guidelines for what works, what doesn’t, and why. And once you learn the rules, you can start experimenting with their boundaries. Balance, structure, colour theory, All those things hold true regardless of style you draw in and with writing, like graphic art, there will be some concepts that appeal to the lowest common denominator that they grow out of once they get a little world experience and maturity. Sometimes lightning strikes and something gets flash-in-the-pan popularity even though no one can figure out why, but those things don’t stand the test of time; they’re forgotten as soon as a new fad comes along. Quality is what sticks around.

After all, which film from 1991 do you have a better recollection of, Beauty and the Beast or Felix the Cat: The Movie?

Some person a couple of years ago on a forum was saying that villains shouldnt be the pure evil jackass types and that maybe they should have some motivation that is understandable or that you could even agree with. That the pure evil villain wasnt interesting. Then i pointed out the baron harkonnen from dune to them. That guy was a pedophile, a murderer, a manipulator, and to top it off he was so morbidly obese that he needed special anti gravity things on his body to walk. But he was so smart, and he was still an interesting character and the book dune is a classic that has spawned games and movies, and i do believe frank herberts son is still making new dune books though he may have finished the last one by now.

I’ve no doubt that Conan’s a Marty Stu, which is why I hate him. What I hate about him the most is what he did to animals. And so, I wish that those beasts killed him brutally.

Well that was a fun read, I never knew about half of this stuff (although it seems kinda obvious now), but yeah, a perfect character can be very uninteresting and boring if done wrong, thanks for awesome advice! :)

The first few paragraphs were interesting, but then I just looked at the pictures :D

Can you become a preacher? Or a professor? Or both?

Or maybe an ambassador. You’d be like “guys guys guys, chill the fuck out while I reference pop culture.”

This was well thought out and really interesting to read. I thoroughly enjoyed it.

A Mary Sue, technically speaking, is an original character inserted into another work (i.e. fanfiction and similar). I know it’s a nitpicky distinction, but it raises one of the ways in which I think the term is misused.

You expect the protag or hero of a novel to be interesting in some way, and for good parts of the story (or narration) to revolve around them. The character doesn’t have to be interesting in terms of superpowers, or even a Badass Normal, but it can be. The same isn’t true in a fanfic, which people are likely to be reading in order to read a story about their favourite characters, not an inserted character.

Maslow’s Pyramid of Relatability still applies (you rock for sticking that in), but I think “Mary Sue” is often thrown around to try to make writers feel bad for writing any kind of ‘awesome’ or ‘special’ character at all. IMO, to be a Sue in the broad sense of the term, the character has be awful to a degree that do serious harm to the story. If they’re knocked back for being perfect and self-satisfied about it, there’s still a story. If everyone loves them for being perfect except for a single rival who is quickly humiliated, there’s no story.

I don’t think the Commander is a Mary Sue. He’s very obviously crafted not to be.

Umm no.

Although the term Mary Sue originated in fan fiction, it’s kinda mutated into a pan-dimensional all encompassing term which means whatever you want it to mean. Generally, it refers to flawless and idealised, shallow characters. Sure, you can argue from the purist point of view and say it means X and X alone because that’s what it originally meant, but try going in to a bar and calling people gay because they look happy without explaining yourself and see if they react. Unless it’s a gay bar cause I don’t think they’d mind too much. Basically, the meaning of a term isn’t concrete and changes sometimes. But when lots of people try to change it it gets confusing.

Being a Mary Sue doesn’t always have to be a bad thing, though. If done right, they’re relateable enough. Harry Potter’s a fairly big “sue” in most senses of the term, but in the context of the story that’s fine because it’s not exactly trying to be literature. It’s a story. It’s meant to be fun. Deal with it *sunglasses*. Bella Swan is also a sue but I won’t even bother going in to that because oh god.

And to say the Commander was specifically designed to NOT be a Mary Sue is kinda misleading. I seriously doubt Squid developed his character by comparing it to a yardstick and making sure it doesn’t match up too much. She designed a character, plain and simple, and to be honest that’s the entire point of this entire post.

Bella Swan is a Mary Suit. She’s a Sue for the reader; a characterless, voiceless void for the reader to fill so they might live out their vicarious romance with “Edward’s Perfect Face”.

No, you deal with people who bitch about things that they want to bitch about. It’s their right to. I mean, would you want me taking away your right to opinion?

I couldn’t read all of it. Iron Man II spoilers. Boo. :(

Basically just that it was the most disappointing movie of 2010

Both Iron Man movies were better than both of Nolan’s Batman movies.

Oh damn, you seem to have transported here from an alternate dimension where Nolan apparently released a Batman movie in 2010. I don’t want to alarm you, but in our dimension Iron Man II was a flat and uninspired piece of garbage.

Gotta say though, if you think there was anything redeemable about the second Iron Man movie beyond “it’s fun to watch things explode”, don’t even bother reading this post, you’ll probably just think it’s a waste of your time.

Did Iron Man run over your cat or something

He wasted my $13 and precious time.

This is exactly what I needed to read right now! I thank ye, oh queen of awesome and good timing!

I <3 Steve Buscemi.

Classy, classy man.

tl;dr The artist is going to start drawing more comics with Mr. Fish because of all the fan fiction the community has written about him. It was too sensual to resist.

I may have to draw steamy anime-styled porn of that post.

Or maybe I’ll just keep it to myself, in my secret happy place.

Fantastic post. MGDMT is becoming a “came for the pop culture, stayed for the insightful reading” situation. Keep up the good work, on both fronts.

This was an excellent and insightful read! Thank you for taking the time to write this, I learned a lot.

I have a similar opinion, except about cliches. Like, the description/phrase type not the plot related one. I had this one tutor who would pound me relentlessly for using them when to be honest I probably wasn’t. Her general opinion is if the description has been used before – ever – it becomes a cliche. No matter how benign. Dark and stormy night, yeah, definitely a cliche and it’s impossible to use unless you’re doing it to be silly, but seriously this woman would ride me for things like describing the sky as “dark” or some inoffensive variation thereof. Admittedly it was a little dull, but that’s how the sky was and I’m not purpling this shit. There’s only so many ways you can get that across to a reader without being a pretentious asshole and overwriting it. Especially if the focus of the scene isn’t the sky but what goes on underneath it.

She whined at me once for something that went a little like “copper coins and sangria” to describe the taste of blood. “WAHHH NO YOU CAN’T SAY THAT CAUSE BLOOD TASTING LIKE COPPER/METAL/SWEETISH IS A CLICHE”. It’s what it tastes like, I can’t do anything about that. To describe it as otherwise would just alert the “LOL YOU DIDN’T RESEARCH X ENOUGH” crowd.

So yeah I forgot where I was going with this, so, in conclusion: Also cliches.

Sad. Clichés become cliché because they’re effective. I wouldn’t go around using them willy-nilly without any consideration for how they impact the flow of your writing, but I wouldn’t, for example, avoid calling something “rock-hard” just because it’s been done a million times before — like most clichés, it’s a succinct method of putting a specific image in your readers’ heads.

“WAHHH NO YOU CAN’T SAY THAT CAUSE BLOOD TASTING LIKE COPPER/METAL/SWEETISH IS A CLICHE”.

It would be entirely inappropriate of me to suggest punching the offender in the mouth and ASKING THEM what blood tastes like.

By referencing Maslow’s hierarchy in this context, I think you have taught me more about good characterization than all of my short story creative writing classes -.-

I’ve pretty much given up on writing as a profession (having found a new career that is remarkably fulfilling), but I may have to try writing something this weekend with the hierarchy in mind… my stories had the necessary conflict before in a vague sort of way, but structuring it per the pyramid could bring a lot more focus. Thank you!

Now that was an interesting read. Writing a comic myself, I am often in doubt if the characters I create are interesting, relateable and/or believeable (and preferably, also likeable). The Pyramid concept seems really interesting and helpful in that concern, and I feel reading this has really helped me. Also your thoughts on characters as a mouthpiece for the author’s ideas, something I’m sometimes slightly worried about if a character has similiar ideas to mine.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts on these subjects.

I admit that I don’t usually read long bits of text on the Internet because I find it uncomfortable. But when you write something, I will read it start to finish, because you do have a way of transporting information in an effective and entertaining manner, both in this format and in your art.

I think that part of why some people are so quick to scream “Mary Sue” is that good writers are damn rare. It seems to me that making a competent character likable beyond a cursory glance is one of the harder exercises in writing, and a lot of people don’t seem to be familiar with the idea that it can be done. But that’s just my personal conjecture.

That said….

Are you crazy, girl? Why do you add to your inhuman workload by writing essays? Screw the critics, get some sleep!

Someone should post this on /tg/ for all to see as it’d help a lot of newbies.

Same here though, you made me realise something I’d kind of lost hold of with my story-writing, and I now have the inspiration to get my book project back off the ground.

So where is this art blog (or is it hiding in this site) because you’ve lately been tackling some interesting subjects quite well, and I’d be greatly interested in looking at some of the things you’ve written about in the past. I’m actually a little surprised why no one else has been able to be this logical about some of these subjects, but then again, it is the internet.

It’s just coelasquid.blogspot.com, but it’s in a pretty sad state. I was never quite sure what I wanted it to be so I would just let it sit for months at a time with no updates. and Blogspot is a MAGNET for weird Asian spam, so I kind of avoid it now.

Awesome… As an up and coming writer (in my own mind) I really saw some amazing ideas that I could put into my own characters, and honestly couldn’t disagree with any bit of what you’ve written. People don’t read or watch stories so they can feel worse about their own lives cause the other guy is perfect. BORING! They want to see people taken down a few notches, or at least be able to go, “Awww, I guess being rich and famous has it’s share of issues too.” Then they hate their own life less regardless of that fact that it IS better to be rich and famous. They can just pick up the latest esquire or rolling stone to find out the mountain of mental and legal problems our modern day hero’s have.

ANYWAYS… I was wondering if you could post the rest of that article though, AND maybe post more storyline suggestions like this every once in a while. It was an enjoyable cherry on the top of the awesome testosterone filled cake that is your comic.

Thank you.

D: You mean my character DOESN’T have to be boring to be good?

WHAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAT?

This is the best article I have ever seen on this issue. THANK YOU for writing it.

Nice read. :-)

An interesting read. I’ve always thought stuff like this was pretty obvious (hell, looking just at how many powers he has FORGOTTEN makes Superman a boring overpowered character, but some writers still manage to write great stories about him that are more than “Superman punches this month’s villain really hard”), but I’ve never made the connection to Maslow’s Pyramid. Very educational.

Also, you’ve read Major Bummer? +2 cool points.

No matter what surplus or lack of power a character has, they can only be as interesting as the challenges they face.

A really good writer can even make “Superman punches this month’s villain really hard” into an interesting and challenging story.

I will once again assert that Superman vs. Muhammad Ali is one of the top five Superman stories of all time, in no small part because Superman resolves a major part of the story’s conflict by punching out a starfleet.

That was a wonderful essay! I especially loved your application argument, because it’s so true. Reminds me of something Chief Editor at Marvel said about Mary Jane, Spiderman’s primary love interest at one point. “Spiderman having a supermodel/actress for a wife is ridiculous, no one can relate to that!”

My main sticking point with that line of reasoning is that while sure, having a supermodel/actress for a wife isn’t exactly common, does that mean Spidey will end up living the high life off his wife’s career and fame? Pff, not likely! In reality, being an actress/actor can be a real struggle unless you make it big. There’s no health benefits, no retirement plan, no steady income. Sometimes you have to work two jobs to make ends meat just so can stay in a high profile area to stick around for auditions. With a good writer, that means Mary Jane will end up being one of those struggling actresses, because in that there’s conflict (and in the Spiderman movies, with the 1st movie at least that was the case) See? Description =/= Application.

Thank you! Years ago the enormous attempt at defining what a Mary Sue was had troubled me. None of the definitions of the time or the countless litmus tests seemed to get at the heart of the matter. I knew it wasn’t anything to do with specific characteristics and after mulling over it, I could only come up with the notion that it all boils down to perfect=boring. While I think that is technically true, you have more clearly distilled the problem behind what is a “true” Mary Sue right here, with far better insight and clarity than I’ve ever had, while at the same time explaining why it’s all too easy to sling Mary Sue onto a character you simply dislike and how to avoid it.

I’m also with one of the previous posters; you’ve just taught me more about storytelling in one essay than my high school creative classes and everything else I’ve read on the subject combined. I also loved the art tutorials you put up a few weeks ago. I hope you’ll eventually do more things like this! I love your comics but I equally enjoy the information you’re willing to share with us. Keep it coming. :D

Oh, hey… weird but sudden thought… you should maybe go to Wikipedia and put some of this into the Mary Sue entry (link back to this post in the references portion of the page and voila!) No, Wikipedia isn’t perfect and clearly anyone could edit your work out BUT I sincerely think this is an important bit of information and that would be one way to inform the masses. Even if you don’t feel like doing it, I sincerely think someone should!

Edit wiki yourself then?

Wow, for the longest time I thought no one else understood this. You have restored my hope in humanity again… until I go to the newest ‘blockbuster’ and puke at the terrible writing.

I absolutely love this. I agree with everything you said. I want to marry you.

That’s not creepy at all…

Don’t be jealous, Titan.

How would you feel if someone just ran up to the person sitting next to you and said “Marry me?” without so much as seeing their face before? I’m just saying that it’s a little creepy.

This is the internet, Titan. Creepy is normal here. Get used to it if you want to stay.

If I may say so, I think this ranks in the top ten blog posts I have read. Ever. You’ve approached the ubiquitous “Mary Sue” subject – something I’ve thought a lot about – from a completely different angle than I’ve ever considered. Thank you!

When I got to the bit about Maslow’s pyramid of needs my brain inserted “head” after “pyramid” and I had a serious case of the giggles the whole rest of the way through.

Apart from that, I enjoyed it in the intended manner.

Dear God, you said that and I got an image of the Maslow’s pyramid in the shape of pyramid head… with the colors and everything. I’m going to be randomly laughing about that forever now.

I’m sorry! Don’t hate me!

Don’t worry, I like to laugh at random and awkward times. Makes life more interesting.

That happened to me too :( was like “HOW PYRAMID HEAD IS RELEVANT OH WAIT IS HE EVER IRRELEVANT?!”

This was a really fantastic read. Although I’ve always been very aware of marysues, I never realized that what it boils down to in the end is how the reader connects with the character. You talking about the pyramid and giving these great examples like the Major Bummer comic and Sten (ohman I laughed. you got me) were really effective. Thanks for writing this. It’s really a great thing to keep in mind not just when throwing around the word marysue but also when evaluating what makes a character good in the first place.

Wow, after the first couple of paragraphs my brain just stopped processing. Then I had to start again. xD

At risk of causing people to lose a significant chunk of their lives, TVTropes is a pretty good treatise on the whole Definition of Mary Sue thing. Their Laconic entry sums it up pretty nicely: “An implausibly perfect/competent idealized character.” In the end, it’s about wish fulfillment. Nothing to worry about == Nothing to write about.

Apparently Iron Man 2 didn’t quite hit everyone in the same emotional range, though. I found it perfectly well. He’s got a couple hours of life, he’s basically wasting them away in debauchery (more so than usual, at least). It was meant to be short-term. Plus, nobody goes to the movies to watch Iron Man: The Legal Preceedings. :D

My point is that the second movie the writers seemed almost afraid to push Tony down in the muck too much. I think the two side by side make an amazing case study because the first one did everything right to make a sincerely good comic book movie while the second one did almost everything wrong. Iron Man II Tony is like Bella Swan for boys. He is wealthy, attractive, charismatic, the public adores him, women are all over him constantly, he’s got one of Marvel’s completely asinine “Smartest person on earth” chips”, no matter how much he abuses the people close to him they are always ready and willing to forgive him, the only authority figures who oppose him are played out as incompetent strawmen, and the vices they gave him as an attempt to bring him back down to earth are so easily dropped that they’re completely negligible. They touch on his alcoholism, but in Movieland a firm dose of “Hey don’t do that anymore” “Okay I won’t” is apparently all it takes to get that monkey off your back. He’s “dying” but it’s completely an issue of telling us without showing us. They give us a countdown but he doesn’t seem all that bent out of shape about it. Before the blood poisoning issue can throw off ability to keep up appearances and mess with his illustrious life of formula one racing and mansion keggers, Samuel L trots up and hands him a patch for what ails himm as if to say “Remember that problem you had? You know, the only problem? We figured it was distracting from your ability to be perfect and awesome too much so we wanted you to have this.” And then before you can even begin to toy with the idea that a temporary fix to the problem might put some limitations on him, he finds out that his father has broken the laws of 9th grade physics to gift him with the blueprints for a new element that will completely do away with the only mite of conflict in his life.

Now I’ll be the first to admit that my favourite genre of story is probably “retribution”, but when I’m evaluating a character I look at the good things that happen to them, the bad things that happen to them, and how hard they work to get what they want. If you’ve got all of those things in pretty good balance, you’ve written a satisfying story. If a character has an awesome life handed to them and nothing challenges them, that’s not satisfying. If a character has a terrible life, they work hard to improve it, and die without reaping any benefits that’s not satisfying either. If a character has their face rubbed in the dirt, does a Rocky montage to the top and takes on the world, everyone gets to leave the theatre feeling happy.

Yes, I completely understand that there are millions of people out there who like to see Tony Stark be the smartest, richest, strongest, handsomest, wittiest, most popular, best dressed guy who can lay the smackdown on anyone who tries to bring him down a peg, but millions of people legitimately enjoyed Twilight for completely non-sardonic reasons too. That doesn’t make either story well written or ether group of fans any better than the other.

“Iron Man II Tony is like Bella Swan for boys.”

I knew there was a reason I wanted to punch him off the screen.

First off, I want to say that I do like this article in general, as well as your webcomic. But in the case of your analysis of Iron Man II, I cannot disagree more. You talk about how Tony doesn’t seem bent out of shape about the whole dying thing since he’s racing cars and throwing keggers, but the thing is, Tony reverting to his old “F reasonable behavior, I’m Tony Stark, I do what I want!” IS how the whole dying thing is affecting him. He’s masking his worries by reverting from the more responsible, trying to better the world Tony Stark he became in the first movie into the impulsive behavior indulging, risk taking Tony we saw at the beginning of Iron Man I. And by doing so, he’s pushing away the one woman he truly cares about, Pepper, and eventually gets to the point where his rash behavior results in his own tech being taken by his best friend and made available to others, something that NEVER would have happened when he was on the top of his game and serves as an example of how the people close to him don’t simply let him get away with anything. Letting the details of your powers get out when you’re a superhero is bad, letting enough details of your powers get out that people can replicate your powers is even worse. Especially when those people want to take you out, both economically (Hammer) and personally (Vanko). And yes, Nick Fury waltzes in and hands him the blueprints to the cure, but by that point, Tony is beaten, he’s got no idea how to fix things himself, so he needs help. I don’t know how it would be better for Tony to have batman’d up the cure all by himself, all that would do is show how he can handle any problem that comes his way alone. Fury’s help doesn’t even solve the only bit of conflict in his life, but merely allows him to face the next one, namely Vanko controlled drones and Warmachine, and Vanko himself. Which as I said, is a issue he wouldn’t have had if not for the way he reacted to dying.

So yeah, that’s my take on the matter.

I understand what they were going for, but I feel like they failed miserably at it out of fear of making things too bad for him or bringing him down too far. They succeeded with it in the first movie, and scraped past with a construction paper cutout in the second, true to sequel form. That’s what made the first movie a solid piece of cinema and the second a fluff popcorn flick. I’ve noticed it seems to be a sign of a young or inexperienced writer that they’re afraid to let their character be the bad guy or bring them down too low, and either give up the story or it gloss over when things start leading up to something too tragic or climactic, and that was what the whole movie played out like. Completely barring the other issues they had writing it, like diverting attention in the climax by focusing the majority of it on faceless drones, which would be kind of like making a final showdown with Darth Vader 75% Luke smashing Battle Droids, and how most of Vanko’s character was pretty transparently tacked on after the fact, as though the script just had blank holes that said “let Rourke fill this part in when he shows up”.

But yeah, like I said, I honestly feel like Tony is Bella for boys in that movie. I mean, you can make up a big list of all the tragic issues Bella had to deal with in those books and how many times she was in mortal peril, but that alone doesn’t make for well-crafted story.

The thing is, the way things were going before Fury stepped in, Tony was on the fast track to dying alone and friendless, with his rival taking over his work and the dude who hates his guts laughing at his funeral. As for the final showdown, I’m personally torn on the matter. While a slugfest between named characters is what people have come to expect, there’s something to be said for a quick, lethal battle, especially coming after a longer action sequence. It seems the final showdown is a consistent weak point for the Iron Man movies.

Saying he was “alone and friendless” is like saying your parents have disowned you when you’ve disappointed them. Or like saying your friends all turned on you when they take your keys away if you’ve had too much to drink at a party. There was almost nothing in the way of reconciliation between Tony and any of the people he turned away other than “Oh that completely incompetent guy who didn’t like Tony turned out to be evil, Tony was right after all, we should all be his friends again.” He didn’t have to do anything to earn their trust back and his rival was such an utter buffoon it was ludicrous that they even try to present him as a threat. No story worth it’s salt matches the hero against antagonists that are lesser than themselves. The interest comes from seeing how they shape up to overcome unbalanced odds, if you use every opportunity your antagonist comes up to spell out what an incompetent loser they are, the threat evaporates. You end up with a Team Rocket or Wile E. Coyote situation where the “antagonist” is more sympathetic that the hero. But in the case of IM2 Hammer is made out to be such an unlikeable dick they couldn’t even get away with that. Rourke’s character was probably the most sympathetic player in the story, and he was handled so stop-and start with character leads vanishing into nothing and loose ends abound, I’m inclined to believe at lot of the characterization was added after the fact by the man himself (at the very least that was confirmed to be the the case with the cockatoo, they tried to tack that in after they signed him on because he said he wanted it to make his character less of a one dimensional thug, which completely explains why they had no idea what to do with it and basically ended up killing two birds by the end)

It is a proven fact of storytelling (and life in general more or less) that people do not care about a faceless anonymous mass as much as they do about one character they’ve grown to know. It’s why feed-the-children adverts hold one kid in the camera and tell you their name and life’s story, and why celebrity drama invariably gets more attention from the general public than overseas disasters. This is not to say you can’t have a character tearing through an army of anonymous drones to get to the big bad at the end of the tunnel, but if you use the majority of your time and budget focusing on that, you effectively defuse your climax. It was a waste of a good character to spend the bulk of Whiplash’s final confrontation focusing on Michael-Bay esque bot smashing and cements the scene at the race track as the most climactic point in the movie.

Oops, there was another response to my post, should have checked sooner.

Anyway, certainly there was something in the way of reconciliation of Tony with his friends, it’s the same thing that pushed them away in the first place, his response to dying. Without a change in that attitude, it’s not going to happen and there’s little to indicate he’d be able to simply change that. Secondly, do you really call saving the Stark Expo and both of his friends while demonstrating that he’s got his head back on straight doing nothing in regards to earning back their trust? And since Vanko at the end there had both Iron Man’s and War Machine’s numbers, and would have beat both of them if not for their use the explosive reaction of their repulsor rays combining, it’s hard to say he’s lesser than Iron Man.

I’ll just accept that you enjoy stories with immensely shallow character development and move on. I mean, no shame in it, I do too. You just need to recognize when characters are shallow. Tony goes throught the motions, but as I’ve pointed out time and time again, he just doesn’t go through the struggle. Compare it with something like the Green Hornet, same story, billionaire playboy who pushes around his best friend and sexually harasses his assistant, but he gets shit for it, he pushes them away and has to apologize and own up to his shortcomings before he can get them back in his corner. The people with authority who disagree with him are obviously competent and when they’re disappointed with him it carries emotional gravity without making the story any less fun. He has character flaws that go further than “I’m too awesome” and by the end of the story he’s still a rich happy-go-lucky player with the same flaws, but he’s grown enough to have a better understanding of boundaries and consequences. Same dynamic, same tone, but done right.

Simply repeating yourself doesn’t automatically make you right, and the fact that you’re bringing up the mostly panned Green Hornet as a example of good storytelling doesn’t do a lot to help. I could repeat again the problems Tony faces, and how his actions at first just create more problems for him until he changes, and how most of what you said about the Green Hornet could apply to Tony, but it’s obvious we’re not going to see eye to eye on this one.

example of good storytelling doesn’t do a lot to help.

Grammar aside, that’s more or less conceding that Iron Man 2 is bad storytelling. That doesn’t mean you can’t like it, it just means it’s poorly written. No accounting for taste, and all, like I said, I like Jason X, I just don’t try to pretend it’s a good movie.

Replying to my own post since I am unable to reply to yours.

“Grammar aside, that’s more or less conceding that Iron Man 2 is bad storytelling.”

No, that’s saying that holding up Green Hornet as an example of good storytelling throws doubt on your ability to distinguish between good and bad storytelling.

Whatever you say, birthday boy.

…Birthday boy? What is that supposed to mean?

I first want to say, I love how you wrote your analysis, and I agree with much of what you say, especially when discussing “Mary Sue” characters. I also agree mostly with your opinion on Iron Man II: though I enjoyed it, it was missing a lot. You helped me pin point what I couldn’t really figure out (nor cared to figure out, but am glad to have learned it.)

The one thing I do disagree with, and it may just be that you didn’t want to get into a different subject on this part of the thread, was how you defined a “satisfactory story.” I guess I mean, I don’t disagree totally, but I’m hoping you’re not speaking in absolutes. There are many stories I’ve read that have the protagonist work really hard, only to fail in the end, and yet, I still found the books wonderful.

I’m just gonna toss in the quote for reference, so it’s not hard to find.

“If a character has a terrible life, they work hard to improve it, and die without reaping any benefits that’s not satisfying either. If a character has their face rubbed in the dirt, does a Rocky montage to the top and takes on the world, everyone gets to leave the theatre feeling happy.”

*Spoilers*

For example, The Idiot. This story was absolutely wonderful (not just saying that cause it’s a classic.) The Prince has lead a sickly, but decently happy and innocent life up until the point he returns to Russia. It all goes to hell then and he never really recuperates from what happened to him after coming “home.” He leaves a broken and defeated man, having gained really nothing from his return, and leaving in poorer health than he came. He gains nothing but the sick realization that the world is cruel and horrible place, and must return to the innocence he once lived it. Was the story unsatisfactory because the hero gains nothing? I don’t think so, but I guess some might be upset by that (well, I was upset, but I wouldn’t want the story to be all rosy–that’s not the ending meant for the story.)

Another: Fight Club. The main character (whose name we never know) goes through all this crap and ends up never having his freedom again. It’s a big downer, but you wouldn’t really feel like the story was being true to itself it all ended “happily ever after” as the film did (the only flaw I found in the movie, in fact, was its divergence from the novel at the end.)

My last example, and it’s a bit more lame, is The Picture of Dorian Grey. Here, none of the characters win…well, except if remember correctly, George gets out unscathed. Everyone ends up struggling and striving towards their own goals and fails miserably (the artist Basil and his desire for Dorian’s attention and friendship, Dorian himself and his greed and narcissism, and the actress who thinks Dorian’s in love with her.) But was the story good? Was the ending satisfactory? I think so.

I apologize if I’m just being obtuse and should know that there are exceptions to the statement made, but I thought it would be helpful to at least list a few examples where a story works when no one wins in the end. I like how well you analyze an issue, so I’m sure you’ll have a good reply (well, if you feel like it.) I have also not visited your site prior to this, but I certainly intend to check out your comic now. I hope I don’t come off as rude! I’m not trying to be ;)

I think you might be reading further into what I’m calling a “satisfying story” than I intended. Stories don’t need to have happy endings because real life doesn’t always have happy endings, and often some of the most profound stories don’t give the protagonists their happy ever after. My point is more that if you torture a character for no reason and no one ever learns or gains anything, it’s going to frustrate your audience. I use Rocky as an example because it’s the simplest textbook application of that formula, but I’m not saying every story needs to be Rocky. That would be like saying “here are the primary colours, never mix them”.

What I’m saying wears on the audience are things like, say, Charlie Brown kicking the football. It’s a classic gag, but after a while it got frustrating to watch. It’s like seeing someone put their hand on the stove over and over again. If Charles Schultz wrote a Charlie-and-football centric story, it would probably have to either end with him kicking the football, him realizing he’ll never kick the football and walking away, or him realizing that it makes Lucy happy to think she’s tricked him, so he goes on kicking at it and missing because that’s the game and if he stopped it would be over. In two of those three scenarios he doesn’t get what he wants, but he’s made some sort of character arc. Actually, if you read the early Peanuts comics Charlie Brown was kind of a dick so when bad things happened to him you didn’t feel too bad about it. Over time they wrote out his attitude but kept all the negativity towards him, so you end up with a frustrating story about a character who never gets to succeed. Peanuts cashed in on this formula for decades because it was a daily strip about preseving the status quo, that kind of writing doesn’t typically stand as a story and that’s why many of the TV specials were about things like him kicking the football or talking to the little redhaired girl.

The stories you’re mentioning have characters who are flawed enough that you don’t mind seeing them not get what they want, or they’re learning something achieving some goal even if it comes with negative consequences. If a character spends the whole story being pleasant and working hard and helping their fellow man, then they fail to achieve that goal and end up with nothing, it’s going to frustrate your audience unless it comes with a “and they learned to be more aggressive about their goals” type of moral or something like that. Sometimes you can have a character chase a goal and never attain it, but realize in the journey that they don’t really need it. Sometimes you can have a character chase a goal and achieve it, and realize they were better off before. all of those stories can be satisfying. What doesn’t work is just constatly abusing a character who doesn’t bring it on themself without giving them any kind of payoff in the endgame.

Consider some possible storylines;

-Kid is bullied in school, he uses it as incentive to toughen up and stand up for himeself so he doesn’t get bullied anymore

-Kid is bullied in school, he realizes the bully is picking on other kids because of some personal insecurity and ends up befriending him

-Kid is bullied in school, the violence escalates, the kid ends up being stabbed and dying, but because of his death the school cracks down and makes sure no other kid will ever have to go through that kind of harassment

-Kid is bullied in school but by the end tof the story he realizes that school means nothing in the grand scheme of life and decides it’s not a big deal because he’ll be off to bigger and better things in a few years

-Kid is bullied in school, he uses it as motivation to pull himself together and become popular

-Kid is bullied in school, he uses it as motivation to pull himself together and become popular but ends up becoming a jerk setting himself up for a fall because he forgot who his real friends are

-Kid is bullied in school, that happens forever with no resolution

Which of those would you want to watch? Not all of those scenarios are happy or end with the protagonist getting what they want, but most of them are satisfying because someone got something out of the protagonist’s struggle. Only one would leave people wondering why someone even bothered to write the story down. Of course, it all depends on context and how the writer treats the situation, but generally, if you abuse a character too disproportionately you’re going to frustrate your audience away.

Ahahah I hope that the webcomic doesn’t let you down too much if you’re new to it, for all this writing about storytelling, MGDMT is more or less a fluff gag strip. This is all stuff I’ve picked up through working on other projects :P

That’s a lot of good points, and well elaborated. But I think the key point is there’s no bad characters, just bad writing. Mary-Sue gets a bad rep because she’s so very frequently used as a tool by inexperienced writers, while being one of the hardest characters to write well. Identifying with a character’s basic human needs is ‘easy’, but it doesn’t mean the more complex ones are inaccessible to an audience. Just that it takes more effort to make them interesting.

Which is to say I find criticizing a story by calling its characters Mary-Sues ridiculous.

But Jenny, see, Mary Sue is an idiom which refers to a character that can only be made as a product of bad writing. Achilleus was incredibly powerful, nigh-immortal, had anything he wanted… but he’s remembered as one of the greatest characters ever. And if you think he hasn’t been, consider how long we’ve been talking about him.

If a character is well-written, they are by definition not a Mary Sue.

If your definition is “badly written character”, sure. I find the definition “idealized wish fulfillment author insertion character” more relevant both with how the word originated and how the character is usually written.

you should seriously repost this to as many relevant places as you can. This is a brilliant explaination on how to write a good story. An explanation that should really be told to as many movie and game producers as possible. And I know people already gave kudos for this, but still, awesome use of Maslow’s Pyramid. Haven’t seen that crap since High school, and it just works!

What comes to mind when you mention a “believable” character is Scott Pilgrim. He’s a dude with tons of issues stemming from failed relationships, and when he finds a nice girl he likes, he’s forced to fight for his life for her. People with friggin’ superpowers, versus some dude who plays bass guitar and video games. And this fight makes him almost lose everything, which makes his fight to reclaim it all the better. And this is just the condensed movie version, without the extra (albeit interesting) riff raff from the comic! But Scott embodies a struggle many people surely have faced, which is why lots of people like both the comic and the movie.

Personally, I was for the most part unimpressed by Scott Pilgrim as a character. Every character in that story outside of like… Knives… felt kind of like a clone stamped deadpan Daria with an extra personality trait tacked so you could tell them apart. And using video game boss fights in liu of actual character development left everything feeling insincere. Like, coming out of the movie I didn’t really feel like he and Ramona had any kind of romantic connection or that he and Kim had reconciled at all. My first thought when I left was probably “I wish that had been a movie about No More Heroes instead”. It’s true that they theoretically made the right gambles (Win this fight you get the girl, lose it and you die!), but the execution was very connect-the-dots without much there to make it feel like the character was maturing as a person out side of the announcement they make at the end of the confrontation to let the audience know that they have matured as a person.

I understand people’s mileage will vary with this, as many people seem to have taken up a cult-like adoration of the story and act as though you just kicked their dog if they say anything bad about it; it just didn’t leave much of an impression on me (outside of being pretty visually spectacular). I think what people cling to more is more the situation Scott is trudging through than the actual execution of the story, as Marlon Brando put it;

there was a scene in a taxicab, where I turn to my brother, who’s come to turn me over to the gangsters, and I lament to him that he never looked after me, he never gave me a chance, that I could have been a contender, I coulda been somebody, instead of a bum … “You should of looked out after me, Charley.” It was very moving. And people often spoke about that, “Oh, my God, what a wonderful scene, Marlon, blah blah blah blah blah.” It wasn’t wonderful at all. The situation was wonderful. Everybody feels like he could have been a contender, he could have been somebody, everybody feels as though he’s partly bum, some part of him. He is not fulfilled and he could have done better, he could have been better. Everybody feels a sense of loss about something. So that was what touched people. It wasn’t the scene itself.

And, y’know, as a former Toronto resident myself I gotta say I’ve always found the freeloading 20-somethings who live in the Annex and don’t find jobs because they say it would distract from their art but really they just don’t have any reason to cut the cord to be extremely irritating people. So that could be why the story didn’t touch me on the same level as it seems to have gotten to the other college-age kids who watch it. Don’t get me wrong, I had a fun enough time watching it, I thought it was pretty amazing visually, and I appreciate that they put their necks out to make something a little offbeat, but I don’t think I would choose to laud it as an example of great writing.

Honestly I wasn’t impressed as I realized once you look past all the video gameish stuff, it’s a bunch of romance non-sense ala Friends or such. And the increasingly strong feeling that all said video gameish stuff is just a empty glaze.

Though some accuse Scott of being a Mary Sue; cool powers, two love interests, thinks nothing of it. (It isn’t until later where he admits he has some sort of problem)

this. this sums up exactly why i kind of hated the movie (i haven’t read the comics, though). i couldn’t get past this whole…”i’m in a band, i had a dream with a girl and she’s my dream girl, she’s so perfect” because i felt like none of their actions made any sense. why doesn’t ramona talk about her exes? why does he keep doing this crap when she clearly doesn’t give two piles o’ dung about him? why did the “sex bob-ombs” sell out, what does that even mean at the end?

if anything, i felt like the movie defined the term “hipster” for me. :/ it was full of young adults wearing clothing.

Great article. It bugs the crap out of me when people throw around the term Mary Sue to describe characters I create. “Yeah my character is cool. So? Cool people do exist you know!”

The thought I had was the problems people face also have to be interesting. Take for example the movie Casino Royale (Featuring Daniel Craig, not Peter Sellers). Here you have James Bond. Someone who has been made the god of doing everything by Pierce Brosnan, Timothy Dalton and others (I exclude Connery from this list). This movie changed the James Bond character into a human being. He starts out as the stereotypical Bond, breaking the rules and not giving a sh*t, but then he screws up and his job and life are put on the line. But he stays cool and finishes his job doing a number of cool stunts and sleeping with women. So yeah he’s cool again, the invincible Bond, James Bond. But to keep it simple and avoid spoilers for those who haven’t seen it, his next mission takes him to a far off land where he develops a character, and has weaknesses that are exploited, and he falls in love. Enter Vesper, the character that makes Bond a human again, and despite being the hard ass James Bond he now has a breaking point. He wins a card game, but loses the war and someone else has to save him. Now after a hard day’s work he and his new love can go relax. but it isn’t over. Things go poorly in Venice and Bond is truly broken. Then, thanks again to someone else, Bond can get closure and save the day.

Enter Quantum of Solace. This movie has become my most hated movie in my collection because it shows exactly how to take a character with problems and do nothing with their problems. James Bond has the evil bad guy in custody and all is well and good, but he escapes because of a traitor in the organization. He is still sad from the last movie and they tie this into the plot, but only in a way so they can leech off the humanity the last movie made and not create their own problems. So he’s sad and on a murderous rampage because his lover is dead. The movie then goes off to have him chase a completely different bad guy and it turns into a Sunday cartoon with a car chase, a foot chase, a boat chase, a plane chase, and then a show off in a place that looks cool. And all the while things are blowing up and Bond is all “Grr I’m angry and don’t care about anything. I need to take out this bad guy who has nothing to do with my lover’s death.” Then at the last minute, the writers realize this and put in a scene where he gets revenge by capturing someone who has been mentioned twice before, and he is all better.

I just think this is a good example of the fact that problems need solving in an interesting way to make an interesting character. Problems are cool and stuff, but if they just magically disappear without much context nothing is gained. A problem leaving a mark on a person that lasts is a more interesting tool. A character gets into a car crash and breaks his leg, and after 3 weeks of physical therapy he recovers fully is less interesting than the same scenario, but say the character now has a twitch in his foot from breaking his leg that occasionally causes problems while he drives now.

…That’s just my thoughts.

Quick question, now that I’m thinking about it.

I enjoy the CRAP out of the comic, but what does it have to do with the extended lecture on conflict-building?

I mean to say that it seems like most of the things happening in the comic are less a struggle involving Physiological worries, only rarely about the Safety category… it seems to get more common as we go up the pyramid, I admit. I mean, is that to say that you can indeed build a proper conflict on, say, a desire for spontaneity (to pull something that actually does sound intriguing from the top box) as long as it follows to its logical conclusion?

I actually created a character for an OC Adventure contest with the express intent of it sounding as Mary Sue as possible. His name was Jonathan Slain, he was fairly muscular, had green eyes and wore a trench coat. His backstory was formulated to be as ridiculous as possible. Like the reason he became a detective was because his brother’s teddy bear was stolen when they were kids, and Jon vowed to never let anything like that happen again.

Then I was going to play the character as straight as I could, and have him behave realistically in as ridiculous a way as the setting would allow. Then I realized how much of a waste of time it would be.

Interisting post.

I liked your comparison between Drizzt and Sten.

However, I really, REALLY hate Drizzt (because I despise chaotic good characters), and far prefer Sten. Besides, Drizzt worships a freakin’ unicorn!

Little realised fact about unicorns: They’re horses with sharp instruments on their head for the use of goring others.

However, given that it’s Drizzt Do’Urdan, I suspect he worships one of those stupid “sunshine and rainbows and looooooooove” unicorns. Sadfais.

This is the Unicorn Goddess that he worships holy symbol

http://images.wikia.com/forgottenrealms/images/e/e8/Mielikki_symbol.jpg

He worships Sparklelord?

Come on, we’re talking about someone whose swords are named Twinkle and Icingdeath.

What kind of elf is he, again? Keebler?

His rival is more awesome

” Artemis Entreri is a merciless, ass-kicking machine who will F****** RUIN YOUR S*** if you touch him. He is Drizzt’s antithesis: a cold, uncaring assassin who will murder you just because he really f****** wants to and you’d thank him, too, because you just got your a** pwned by the coolest f****** guy on the planet. He enjoys cutting throats. He has a sword that will F****** MELT YOUR FACE if you touch it without wearing a special glove, and a dagger that drains your life if it touches you. He thinks Drizzt would look good as a toilet seat cover. “

I stopped reading this comment after the first string of asterisks

(to clarify, Drizzit is terrible and so is his rival)

Interesting little post, you should have an easily accessible link to this somewhere on the site. But I honestly agree about inner struggles as often with many stories, you see someone go from Zero to Hero yet seem to handle it a little bit too gracefully. I mean the sudden onset of pressures, revelations, etc can get to a guy. And that even at best, part of them is ready to freak out while part of thinks “Whoa awesome.”

I’m probably not going to post a long, sexy argument about how I totally agree with you, so let’s just say you’re amazing and as an aspiring writer I love your comic and your ideas.

From what i glanced at, it looked like a good arguement

this being said: you write a comic about over-the-top, near immortal, hyper-masculine characters, with their cliche storylines, and people are complaining about how they are too generic and unrealistic?

besides every writer incorporates themselves into their characters, you work with what you know

love your comic by the way :)

People who think I’m a man seem to accuse Commander of being my self insert. When they find out that I’m not they accuse Jonesey of being my self insert. Or they accuse me of penis envy and continued to insit that Commander is my mouthpiece. People have also suggeted the same of Jared. It seems like a completely foreign concept to people that maybe these characters are just characters, with no relation to myself beyond claiming squatter’s rights in my head.

Thing is it is foreign to people as I don’t know; can’t believe people are talented enough to make a character that isn’t a stand in for themselves. Sure bits of yourself being in them is kinda natural but no cheesy self insert like Chris-chan (The Sonichu one)

Oh, come on. Chris-chan can’t be real. He’s just a myth they made up to keep people from … liking pickles… too much… ?

… Right?

While I haven’t actually started doing anything relevant beyond a few draft pages, characters and overall mentally writing a plot, a thing I’ve found myself doing is making not just one character representing me, instead what I seem to be doing is split myself apart, giving each character one or more of my traits, anxieties, beliefs.

I don’t think any of them come off as a self-insert, aside from coffee-girl. She needs a bit more development to do so, otherwise, meh. You’re right about patterns– John Campbell in “Hero with a Thousand Faces” proves so! The Commander, Jared, and all your other characters that aren’t tossed in as randoms (aside from coffee-girl) have good character development, especially for a once-a-week. The Commander is well on his way to being very well-rounded! I like your work.

I don’t know how “needs more development” comes off as “self insert”. “This secondary character who has no reason to be the focus of the strip has not had enough charater-centric storylines, ergo they are obviously a mouthpiece”

This is exactly why I thought Bella Swan from the first ‘Twilight’ book was a Mary Sue. My raving older sister lent it to me, so I can only comment on the first book, because one was enough.

The story is set up with a series of possible conflicts for Bella, then is executed in a manner which means none of them ever challenge the character in any way:

—

CONFLICT: A teenage girl moves in with her divorced, rarely-seen father after previously only living with her mother.

POSSIBLE DRAMA: They don’t get along. “You don’t understand me”. “While you live under my roof you live by my rules!” etc

NO CONFLICT: He says he’s happy to have her stay. He gives her a Truck of her own on her arrival. Their home life is easy-going. She still tells everyone she’s lame, but no-one tells her she’s an ungrateful brat.

—

CONFLICT: A girl who says she’s ‘moody’ and ‘different’ moves to a new school where she doesn’t know anyone.

POSSIBLE DRAMA: She has trouble being accepted by a cliche. She’s treated as an outcast. Her moods get her into trouble with staff and the other kids.

NO CONFLICT: She is instantly accepted by her peer group, forms an instant an active social life, and is asked out by every male character within that group. She is also instantly accepted and adored by teaching staff.

—

CONFLICT: A girl starts her first day of school, and instantly sets her sights on the most beautiful boy in school.

POSSIBLE DRAMA: Trying to catch the eye of someone in a higher peer group. Possible rejection. Having to change her appearance is to catch his eye. Stalking etc.

NO CONFLICT: He’s instantly smitten and pursues / stalks her, which also doesn’t cause conflict because it just proves ‘how much he loves her’.

—

CONFLICT: A girl moves away from her mother and her new boyfriend.

POSSIBLE CONFLICT: Alcoholism or drug uses by parents. Conflict with mother over new beau. Conflict with new beau. Possible undercurrents of physical and / or sexual violence.

NO CONFLICT: Daughter only left as an act of self-sacrifice / martyrdom to let mother travel with new beau, because they were ‘so in love’.

—